ACT and the Dunedin stadium

[text-blocks id=”act-party”]

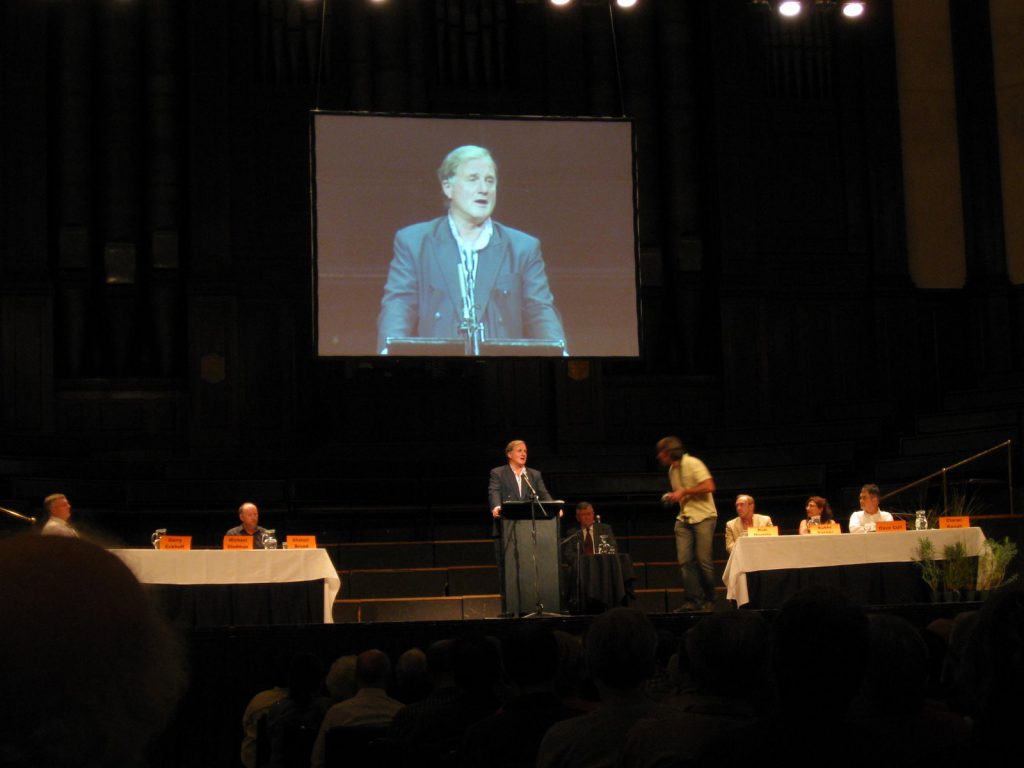

Former ACT MP Gerry Eckhoff delivers a speech at the Dunedin Town Hall, 29 March 2009. (Photo by the author).

Local body politics constitutes something of a paradox. In election years, interest is low and apathy high, with voting turnout under 50% (compared with still a 70%+ rate in national elections). Coverage of councils’ activities in the national media is accordingly minimal, unless there is some particular interest point such as an entertaining mayor along the lines of Tim Shadbolt or Michael Laws. Even in most local newspapers (with some exceptions), coverage of local body politics takes a decided back-seat to the minutiae of central government’s activities. To the best of my knowledge, there is not yet a New Zealand blog dedicated to local body politics, despite the dozens created in recent years (including this one) which are devoted to national politics. This is perfectly understandable: for the most part, local councils perform a function akin to wallpaper. As long as the rubbish is being collected and everything is working as it should do, voters can afford to let their eyes glaze over at the mention of local body issues.

But when a big local issue comes along, interest can arise in a town or region to an extent unthinkable for anything but the most divisive of national issues. On Sunday evening, the Dunedin Town Hall was filled with over 1800 people, including myself, who came to hear six speakers explain why they opposed the building of a new sports stadium beside Otago Harbour, at a meeting sponsored by the Stop the Stadium Trust. The last time I recall the Town Hall being filled for any sort of political event was for the visit to Dunedin by the Dalai Lama in 1995. It certainly outshone the “meet the candidates” forums held in local body election year, which on a good day attract a couple of hundred at the very most.

What is at stake is $155m of money which is set to be collected from Otago ratepayers for the building of the new stadium. But the word “Otago” could just as well be “Auckland” (which saw off the construction of a waterfront stadium in 2006) as it could be the name of any other province in the country. $155m is perhaps not a lot of money spent nationally, but with a population base of only around 200,000 people, this is a project similar in scale to one costing a couple of billion dollars if implemented on a nationwide basis. It is a tremendous sum.

Reasons to oppose “the stadium” are numerous and too many in number to explain in detail here. Speakers at the meeting raised issues on everything from the stadium design (the planned roof would prevent grass growth) and the site (which sits on reclaimed, marsh-like land difficult to build a large structure on) to the fact that the economic benefits of the stadium have been oversold (planned “international concerts” would never eventuate and the building would sit idle for most of the year). Then there is the fact that private investors have hardly been forthcoming with capital for the project, which will leave the local authorities shouldering all the risk and facing a mountain of debt to pay off over the next 20 years (or longer).

As the meeting heard, Dunedin is not a rich city and thanks in large part to the closure of Fisher and Paykel’s Mosgiel factory and the downsizing of Cadbury Confectionery, it has lost a staggering 1,000+ jobs in the last 12 months. Added to the large number of people not “working” in Dunedin (the many elderly, children and students take up a sizeable chunk of the 120,000 population), this gives some idea why the project looks unaffordable.

The ACT connection lies with two of the six speakers at Sunday’s meeting: Alistair Broad and Gerry Eckhoff. Broad is a local real estate agent and is the partner of Hilary Calvert, ACT’s long-time party organiser and stalwart in Dunedin. Eckhoff was an ACT MP from 1999-2005 and in 2007 was elected to the Otago Regional Council. (He also likes to be known simply as a “Roxburgh farmer”). Of the remaining speakers, marketing lecturer Dr. Robert Hamlin, Natural History New Zealand CEO Michael Stedman, former Dunedin mayor Sukhi Turner and DCC councillor Dave Cull, I am only aware of the political leanings of Mrs. Turner, who is left-leaning and as I recall a Green supporter. For the others, I have no idea. But to have at least one-third of the speakers being ACT supporters is a sterling effort in a city like Dunedin, which holds two of Labour’s safest seats.

What was in keeping with ACT in the approach of Broad and Eckhoff was their attention to the decision-making processes behind the building of the stadium. For the past three years, ratepayers who read the Otago Daily Times have become accustomed to reading major decisions only after they were made and without consultation, under the guise of “commercial sensitivity”. (This is despite the small fact that the ratepayers’ money is what is being used). To give but one example, earlier this year ODT readers discovered that they were buying Carisbrook for some $10m and were paying off the Otago Rugby Football Union’s debt (both to the city and other investors) of over half that amount again.

Alistair Broad told attendees at Sunday’s meeting that he had applied under the Local Government Official Information Act to see a copy of the building contract about to be signed with a building firm, which has supposedly a “Guaranteed Maximum Price”. Expecting to be thrown the commercial sensitivity line, Broad had said in his request that he would be happy for the exact figures to be blacked out; it was the wording of the maximum price clauses in which he was interested. His request was denied. Given that the contract to build the stadium is essentially one between the ratepayers of Otago (and especially Dunedin, from where the bulk of the funding is being sourced) and the builders, it seems outrageous that one party to the contract has been blindfolded from seeing the very contract it will be responsible for fulfilling (and paying).

Gerry Eckhoff was clearly very annoyed over the fact that so many of the hearings on the stadium had been held in closed committee. He told the audience that he knew the terms of reference for central government’s $15m underwriting guarantee, but was unable to reveal this because he learnt it in a closed meeting of the Otago Regional Council (ORC). Eckhoff also read portions of the Local Government Act 2002, for which he sat on a select committee as an ACT MP. In his speech, Eckhoff also enumerated the major projects that the ORC was now funding – a $28m new headquarters, its contribution to the stadium and the Leith-Lindsay river flood protection scheme – and concluded that only the latter amounted to anything like core business of the council (regional councils are chief lyresponsible for environmental issues). Ironically, the ORC’s new headquarters are also planned for the Dunedin waterfront and in any other year would be a very controversial issue in itself (as it stands, it is being quietly pushed through while the stadium occupies the ODT headlines).

The meeting concluded with the reading of a letter from ACT leader Rodney Hide, in his capacity as Minister for Local Government. Hide was mostly sympathetic to the meeting’s agenda. It was not up to him as Minister to micro-manage every last decision made by councils, but he was in favour of councils focusing on core business. Big projects were usually bad, but not if there was an exceptional reason. But if there was such a reason, ratepayers should be asked and listened to. If this was not happening, Hide asked to be informed.

Responding to this, the meeting then passed a resolution to invite Hide to Dunedin to scrutinise the decision-making process. I see three possible outcomes of this:

- Hide comes and listens but takes no further action. He does not want to undermine the decision of a National minister who granted $15m for the stadium.

- Hide orders the suspension of the project, by putting it under central government control (as he is entitled to do under the Local Government Act 2002).

- Hide orders a review of some kind of the project, focusing on the decision-making processes and whether ratepayers have been properly consulted.

The third option seems the most likely to me. In 2006, Hide led opposition – along with Keith Locke – to the proposed waterfront stadium which was to be built in Auckland, a project which would have brought a similar financial burden to northern ratepayers. To do nothing in Dunedin’s situation would seem at best inconsistent; at worst, hypocritical. Yet to order the cancellation the project outright would be a bridge too far – Hide supports the autonomy of councils and will not want to become or be seen as an autocrat, especially as his knowledge of the specific situation in Dunedin will be understandably limited.

A suspension of the project pending a review would be the most logical and painless way to deal with a situation which cannot be ignored. Luckily for the stadium opponents, the fact that Hide, an ACT MP who has long campaigned against rates increases, is Local Government Minister means that the prospect of action is infinitely higher than it would be under a National MP who would be content to rubber-stamp the approval for the stadium made by a colleague.

Dunedin’s exact future hangs on whether the stadium proceeds or is halted. A minister from ACT now has the power to decide that future.