Germany’s failed anti-anti-establishment strategy: the case of the Alternative for Germany (AfD)

On Sunday 13 March, the Alternative for Germany party enjoyed stunning electoral success. The party won 15% of the vote in the southern German state of Baden-Württemberg, pushing the Social Democrats into fourth place behind the Greens and the CDU. In Rhineland-Palatinate, a smaller state to the north, the 12.6% was more than double the traditional third parties, the Greens and Free Democrats (FDP). And in Saxony-Anhalt, a state in the former East Germany, the 24.2% won by the AfD, as the party is abbreviated in German, meant that it towered above any other party except the CDU.

But you wouldn’t know it from the reaction of Germany’s political establishment later that day, who were anything but humble and were out to prove that the voters were wrong, Beatrix von Storch, who represents the AfD in the European Parliament, faced proxies on a TV talkshow from both ruling parties in Germany’s Grand Coalition – the Christian Democratic Union (CDU, Angela Merkel’s party) and the Social Democrats (SPD).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RaTAUzlGXRg

Beatrix von Storch, one of the AfD’s seven Members of the European Parliament and whose appearance and cutting manner is somewhat reminiscent of Margaret Thatcher, faced two main critics. On one side was Ralf Stegner, a vocal and unsuccessful Social Democrat from Germany’s northern-most state of Schleswig-Holstein. Stegner led his party to its worst ever result in the state in 2009.

On the other side of von Storch was Ursula von der Leyen, a close confidante of Angela Merkel in the CDU. Von der Leyen, one of Germany’s most ambitious politicians who is currently serving as defence minister, had been found just a couple of days earlier to have plagiarised sections of her PhD.

The anti-establishment as a pariah

“The AfD has reached many voters that we have not. The voters are always right. While we do not agree with the AfD’s answers, we do need to find out why they have been successful in reaching so many voters, particularly previous non-voters.”

Here’s a hint – this was not the response of Stegner or von der Leyen to the AfD’s electoral success. Instead, the pair played tag-team in ridiculing von Storch and the party – and voters – she represented.

Lest this post be misunderstood, I do not support the AfD or the ideas the party promotes, which are not my cup of tea. But I do find the ostracisation of the party by the German establishment fascinating. By treating the AfD as untouchable lepers, elites inadvertently help to boost the party’s martyr-like status with its supporters further. From their own point of view, it is a counterproductive strategy.

The ARD public television talkshow offers an interesting case study in the hostile reaction to the AfD. Von der Leyen in particular seemed to enjoy lecturing her rival in the manner of a schoolteacher giving a errant pupil a dressing down. “Simple and banal answers…empty talk”, was what the AfD offered, von der Leyen told von Storch.

Meanwhile, Stegner, the attack dog for the centre-left SPD, summarised the AfD as such: “You’re against the minimum wage, against equality, you’re for nuclear energy – you don’t stand for anything that’s good for ordinary people.”

A reminder – the AfD, a party not even three years old, had outperformed the SPD in two of the three states, in one dramatically so. The AfD had taken votes not just from the right, but from the left as well. In Saxony-Anhalt, the party received more than twice the number of votes cast for the SPD. In Germany, states are responsible for all levels of education and most police, among other responsibilities, meaning their role is non-trivial.

In an excellent article, Sabine Beppler-Spahl gives further examples of the political establishment’s disdain for the AfD:

The AfD has been called all sorts of names: a ‘shame for Germany’ (Wolfgang Schäuble, CDU); a group of cynics and arsonists (Thomas Oppermann, SPD); and a racial party with racist speakers (Katrin Göring-Eckardt, Green). And its politicians have been treated like lepers. The SPD candidate and prime minister of Rhineland-Palatinate, Malu Dreyer, refused to take part in any TV debates involving the AfD. For her, this boycott was a matter of principle – she ‘wouldn’t talk to right-wingers’. Not only does this say a lot about her attitude towards free speech and political debate, it also shows her contempt for the AfD and those who might vote for it. Despite claims from the SPD that they were still taking the ‘worries of the normal citizen’ seriously, this patronising attitude suggests otherwise. Is it so hard to understand that people don’t appreciate being told that the party they are considering voting for is nothing but a gang of idiotic, racist thugs?

Of course, you cannot expect existing parties to roll out the red carpet for a new political force – a rival. What makes the reaction to the AfD notable is the way established parties are making it out to be so beyond the pale as to be untouchable, by pushing it into the “Nazi corner”.

The media’s contribution

Following the political talkshow on which von Storch, Stegner, von der Leyen and others appeared, late-night news on the ARD, Germany’s biggest public broadcaster, rounded off its coverage of election results with a commentary by Rainald Becker, the channel’s deputy political editor:

Concluding his commentary, Becker said: “There is also pleasing news this evening, voters want continuity….when the democratic parties come to their senses and pull themselves together, this country will keep the AfD out – easily”.

Against the backdrop of the AfD’s results, this comment endorsing the erection of a cordon sanitaire seems stunning. But what perhaps is more surprising is that Becker’s treatment of the AfD as a pariah is not uncommon. Even after the elections, the breakfast programme on ZDF, Germany’s other major public TV channel, engaged in a rather unnecessary public spat with the AfD’s leader, Frauke Petry, after an interview mix-up.

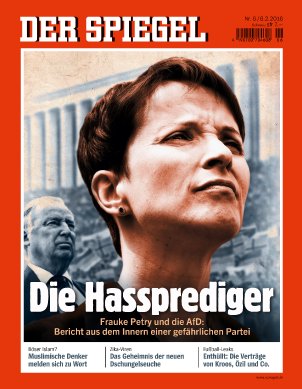

And in the early stages of the state election campaigns, in early February, the Der Spiegel weekly newsmagazine, which plays an agenda-setting function in Germany, ran a deliberately provocative cover with the headline “The Hate Preachers” on the AfD at the beginning of February. The cover’s photo montage was clearly designed to draw a not so subtle historical parallel.

Naturally, the media’s treatment of the AfD has only enhanced the view that there is a “lying press” (Lügenpresse). The Lügenpresse slogan has been one of the clarion calls of Germany’s “Pegida” anti-immigration movement, centred in the eastern city of Dresden. The word Lügenpresse has Nazi origins, in line with the Pegida’s more open racism. (The exact links between the AfD and Pegida are murky, although it seems likely there has been significant crossover in the former East Germany, particularly in Pegida’s home state of Saxony.) This negative coverage towards the AfD has naturally only fed the view of supporters of the party that they are being picked on by a liberal elite. Moreover, it is also counterproductive. Putting the AfD in the same category as openly neo-Nazi parties, the history of which will be discussed below, only gives further impetus to the party’s growing martyr-like, outsider status.

The Alternative for Germany – from technocratism to populism?

Right-wing parties have enjoyed success in Germany since reunification – most notably the the Deutsche Volksunion (the German People’s Union, or DVU), Republikaner (Republicans) and above all the National Democratic Party (NPD) – these parties have been easy to brush off as Neo-Nazis given their openly racist nature. At various times, these parties have enjoyed various degrees of success in poorer states in the former East Germany, with the NPD currently holding 6 per cent of the seats in the rural north-eastern state of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania.

The AfD differs enormously in pedigree to this fascist right in both its history and voter base. The Alternative for Germany was founded by an economics professor, Bernd Lucke, to oppose Germany participating in enormous Eurozone bailouts of Greece. Lucke was more of a technocrat figure and an unlikely upstart party leader.

Despite this, or perhaps because of his non-political background, the party gained credibility as a protest vehicle against the blandness of Merkel, who had moved towards the centre to crowd out her main centre-left opponent. Despite coming from nowhere, within six months of its founding the AfD won 4.7% of the vote in Germany’s 2013 General Election.

By falling short of the 5% barrier to entry, the party was left without representation nationally, but the result boosted the party’s profile enormously which would help it in subsequent elections at state level, which in Germany form something of a permanent campaign.

Following a messy leadership battle, ultimately won by a failed businesswoman, Frauke Petry, the party moved towards right-wing populism with a broader appeal. Social conservatism, symbolised by the party’s anti-immigration sentiment, is now the defining feature of the party. The 2016 election manifesto of the AfD in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate symbolised the longing for old, solid values – the cover featured a photo of a local fortress (PDF).

Nevertheless, the AfD has transcended the old neo-fascist voter segment held by parties like the NPD, going beyond strongholds in the old East Germany. In the European elections of 2014, the AfD’s best result was in an electorate in the prosperous southern state of Baden-Württemberg. And in 2015, the party won representation in the western city-states of Bremen and Hamburg – something the NPD and its ilk had never done.

A home for non-voters

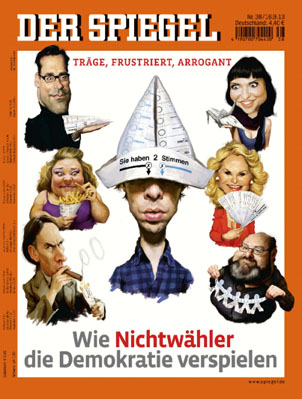

Across western democracies facing lower voter turnouts, every election brings new complaints about people who “cannot be bothered to vote”. In Germany, there was no better example for this than the cover story in Der Spiegel following the 2013 General Election which fretted about the “danger to democracy” that the decrease in turnout was bringing.

In the state elections, however, turnout actually increased – largely because of the AfD bringing in former non-voters. In the southern state of Baden Württemberg, the AfD brought in some 200,000 previous non-voters; the figures were even greater in Saxony Anhalt, the eastern state, where some 100,000 votes came from the ranks of non-voters – an impressive number given the state’s much smaller population of just over two million people. (See the useful graphics in this German article here – the grey sections at the bottom represent non-voters).

The AfD has not been alone in bringing in non-voters – other parties have benefited as well, notably the Greens in Baden-Württemberg. One wonders whether the AfD has helped to galvanise voters of opposing parties – with parties with more clearly defined brands and policies, like the Greens, benefiting disproportionately.

The fact that previous non-voters are voting in disproportionate numbers for the AfD should be an encouraging sign to all political parties that non-voters are not lost forever and can return to the ballot box if they find a choice on offer which is, for them, more appealing.

The Trump effect

Germany’s experience with all of this is not unique. In fact, much of the same elite disdain and media ridicule can be seen in the reaction to Donald Trump in the United States. As in Germany, the attempt to draw a cordon sanitaire around Trump has only made him more popular. Mitt Romney’s attempt to take down Trump in a forthright speech a few weeks ago not only failed to catch hold, it arguably had the opposite effect of intensifying support for Trump.

On the media side, liberal disdain for Trump perhaps has been epitomised best by the Huffington Post’s refusal to carry articles about Trump’s campaign in the politics section, but the entertainment one. Once this position became untenable, every article about Trump had a footnote appended instead: “Note to our readers: Donald Trump is a serial liar, rampant xenophobe, racist, birther and bully who has repeatedly pledged to ban all Muslims — 1.6 billion members of an entire religion — from entering the U.S.”

Where to from here?

Writing on the London School of Economics’ blog, Ben Margulies suggests that Germany is at a crossroads:

The end result may be a German equivalent to a model we already see elsewhere: Increasingly, there is a new cleavage between “establishment” or “mainstream” parties and their populist challengers. In some countries, such as Norway, Denmark or Finland, the populists are being absorbed into coalition politics. In others, like Sweden and now Germany, they are not, forcing the existing parties into increasingly compromising positions and threatening the stability of the political system. (The AfD has already stated that it does not intend to enter a state government; nor will Merkel be changing policy or considering a CDU-AfD pact.) The first scenario has helped give us spectacles like the Danish refugee law. As for the second scenario – well, at least Germany will never run out of Weimar references.

The second scenario that Margulies refers to is already leading to a concerning number of Grand Coalitions in Germany. In fact, this has been brewing for the past decade because of another anti-establishment party which is seen as “untouchable” – the Left Party. The Social Democrats hate the Left Party so much (ostensibly because of its links to the old SED communist party which ruled in East Germany, but also because of personal rivalries as the Left Party grew out of a disgruntled SPD faction) that they have refused to work with it at state or federal levels.

In 2013, this led to a further Grand Coalition at the federal level, even though the SPD-Greens-Left party had a majority in the Bundestag – graphically illustrating the depth of ill-feeling towards the Left Party.

In Saxony Anhalt in 2016, the number of voters who chose the Left Party and the AfD are so great (a combined 34.5%) that the Grand Coalition will also need to bring in the Greens to gain a majority. The parliamentary opposition will consist solely of the AfD and the Left Party as literal outsiders.

Despite its cover, the recent feature story in Der Spiegel on the AfD contained some good advice for the establishment:

One must confront the AfD with rational argument and policy. Establishment parties have to put forth solutions to the large problems that are driving support for the AfD. If the government succeeds in reducing the number of refugees coming to Germany and comes up with a convincing plan for the integration of those migrants who are already here, it could manage to pull the rug out from beneath the AfD.

The advice from Der Spiegel is of course easier said than done: the genie is now out of the bottle and it will be hard to put it back in again. I would argue that the first step in a serious approach towards the AfD is to deal with the AfD as a normal political actor. Turning the party into an untouchable pariah was never going to succeed. The state election results have only proven that the strategy has been an abject failure.

In the short-term, Grand Coalitions are cozy for the establishment elites who hold the benefits of office. In the long-term, they act as a cancer eating away at the parties which enable them. Grand Coalitions are soon seen to be the artificial stitch-up they usually aroster the growth of groups on the fringes who offer something more than blandness. But based on the German establishment’s current approach to the AfD, and to the Left Party before it, a change in strategy does not seem imminent.