Exclusive: Who is Simon Lusk? Lessons from his Master’s thesis on Ecampaigning (2001)

In my previous post, I looked at why Simon Lusk is such an important figure in Nicky Hager’s book Dirty Politics. His strategy to change National from within represents the end which justifies the means – the questionable tactics which have been covered extensively by New Zealand media since the book’s release on Wednesday, 13 August 2014.

In my previous post, I looked at why Simon Lusk is such an important figure in Nicky Hager’s book Dirty Politics. His strategy to change National from within represents the end which justifies the means – the questionable tactics which have been covered extensively by New Zealand media since the book’s release on Wednesday, 13 August 2014.

In this post, I look exclusively at Simon Lusk’s Master’s thesis in politics, which he wrote at the University of Otago in 2001.

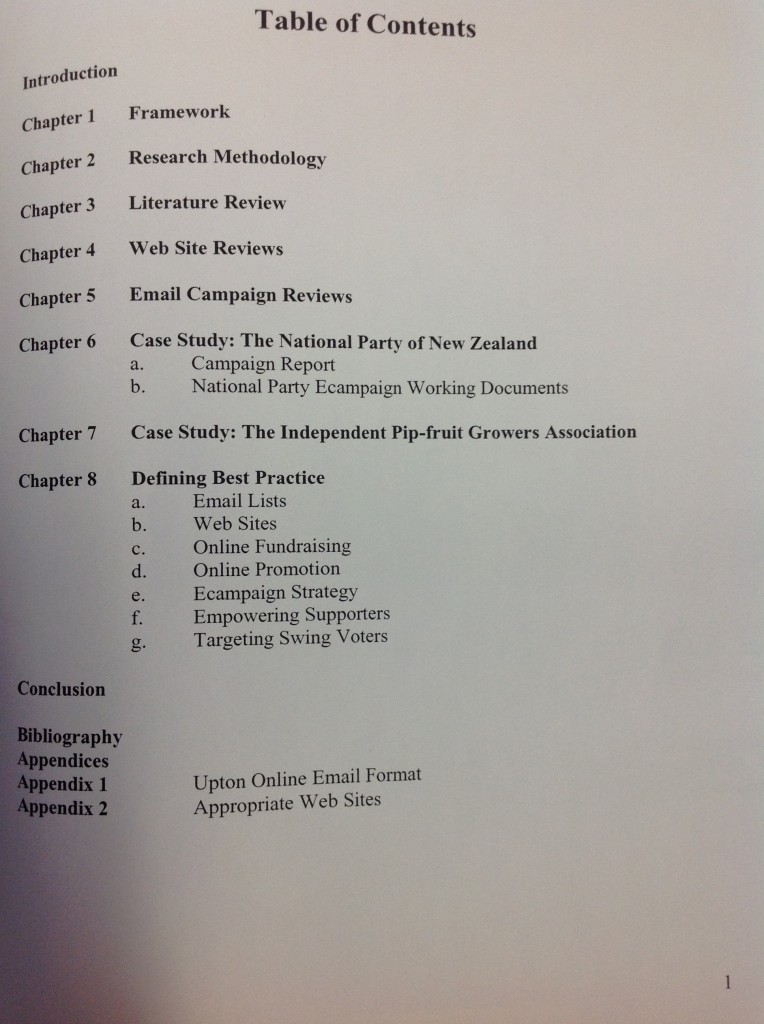

The thesis, called Ecampaigning, looks at how political parties can harness the internet to target potential voters. The 137 page thesis is recorded by the University of Otago library catalogue as being processed in 2002, but from Lusk’s website it is clear that it was completed sometime in late 2001.

Lusk refers to the thesis on his personal website, including his supervisor, former Australian MP Bob Catley:

In 2000 & 2001 Simon completed a Master of Arts in Politics through Otago University, with Prof Bob Catley, a former ALP Member of Parliament, as his supervisor. Bob’s direct approach to campaigns taught Simon a huge amount about professionalism, staying focused and winning.

What is the thesis about?

This thesis is an attempt to answer the following question: How can the Internet be used to win political campaigns. (p. 2)

Ecampaigning is divided into eight chapters, as well as an introduction, conclusion, bibliography and appendices. After chapter three (the literature review), the text is written in a report style with numerous ordered lists.

Chapter 6 is probably most interesting from today’s perspective, because it is a case study of the National Party’s online efforts. This chapter includes details of a September 2000 “request for proposal” for a new National Party website. The manager of the new website was Simon Lusk, in consultation with the party’s “Information Technology Manger”, Paul Smith.

Perhaps unusually for an academic thesis, the treatment of theory seems to be very light, although this may have been reflective of the early nature of the research with regards to online campaigning. In the literature review, Lusk says that the available literature was insufficient as it did “not provide the kind of clarity of strategic thought….The focus on technology rather than strategy remains pervasive, with few examples of successful campaigns available…The lack of literature means that the development of campaign methodology had to go well beyond what was available in the public arena” (p. 13).

Overall, the thesis gives an impression of a very methodical author, albeit one who was in a hurry. On p. 11, Lusk apparently forgot to remove a note to himself “change this to one footnote” and there are a number of similar minor formatting issues throughout the work.

Lusk refers often to unpublished research of his own from 2000-2001, called an Ecampaign Research Diary and to an earlier MPhil thesis he wrote at Massey University in 1996: Developing an Integrated Internet Presence. On p. 10, Lusk writes this 1996 thesis was related to “creating sales online”, rather than on a political topic.

Having been written in 2000-2001, much of the thesis naturally seems highly out of date technologically-wise, but I believe the core themes raised by Lusk remain relevant and often seem prescient in light of recent events. In the following, I discuss and excerpt what I think are three lessons that we can take from Lusk’s research. (Note that these are my takeaways from Lusk’s research and are not the structure used in the thesis itself.)

Lesson 1: strategy should determine technology, not the other way around

A common theme throughout the thesis is frustration with political operators who are using the internet more as a toy than tool.

In the introduction, Lusk writes:

Most political campaigns use the Internet, with email lists and web sites, but there appears to be little understanding of the value this provides. This is not to say that the Internet cannot provide value to a political campaign – it just does not appear to be well defined…

The current focus of Internet use in electronic campaigns is technology driven, rather than strategy driven. The approach seems to be use the technology rather than develop a clear strategy on how to win campaigns using the technology.

This approach is reinforced later in the thesis when the creation of a new National Party website is discussed. On p. 81, a discussion document by Lusk from 2000 is included. It refers to a tender for the creation of a new National Party website, a project for which Simon Lusk is responsible:

Discussion Document

Prepared by Simon LuskThis discussion document outlines the potential for National to obtain long term competitive advantage by targeting individual voters through the Internet. It does not deal extensively with the upcoming election; as this is too close to make dramatic changes or additions to campaign strategy.

The focus is based around an ends rather than a means approach, and treats the medium as distinct – if this is not done then the online offering will be inadequate, and the opportunity lost.

The end that is trying to be achieved is the long-term behaviour modification of voters to have them become loyal National supporters. This is based around cost effective, ongoing individual targeting of people, principally by email with a pragmatic web site backing it up.

Circulation: David Farrar, Peter Smith

What is the strategy? For Lusk, the message is key. He recognises the power the internet can offer by offering an unfiltered means of contacting voters, and also its agenda-setting role. From p. 98:

Controlling Dinner Table or Talk Show Debates

By sending out appropriate email messages to supporters asking them to direct conversations to certain topical issues a campaign has the ability to exert some control on the nation’s political debate. If supporters consistently focus on the same issues or same key themes, with arguments provided by the campaign, they will have a much better chance of swaying moderates or swing voters than if each supporter puts forward their own agenda

Lesson 2: use a two-track approach for supporters and swing voters

Much of Lusk’s thesis focuses on the use of e-mail lists for supporters and potential supporters. While the focus, with headings such as “Why Email is More Important that the Web” may seem a little quaint today, it is not if one sees e-mail as the forerunner of ubiquitous social media such as Twitter, Facebook and blogs. At a time when most NZ parties were using their websites as “brochureware”, Lusk understood that getting their interaction and gaining visitors’ contact details was important, because it allowed party to send their message to supporters in an unfiltered way.

Lusk understood that the message to supporters had to be different than the one to swing voters. He writes about what the National Party’s online aims should be in public (p.59):

Given the National Party’s aim, the ecampaign must target swing voters. …Rhetoric and attacks on opponents should be removed from the public access section, as this is unlikely to help swing voters make the decision to vote for National….All text content that is available to the public should be moderate. It should be reasonable, plausible and sensible, and avoid vitriolic attacks on opponents. While this may not necessarily be in keeping with standard political behaviour it is unlikely that swing voters will respond positively to impassioned attacks on opponents in the standard political form.

Also thinking of swing voters, on p. 69, Lusk warns against using “Chat Rooms, Live Online Platform Writing and Other Fancy Technology” on a main party website, partly because they would attract “odd people who voice their way out opinions – which provides little value to the site and requires a great deal of moderation.”

Later in the thesis (p.104), Lusk describes the problem that “moderate language may not receive the best results” from ardent party supporters. For this reason, he suggests “a supporters’ section, where people who have demonstrated their commitment by becoming members can access a section that provides passionate language that they feel empowered by”.

In 2001, e-mail was the backchannel to talk to committed supporters. In 2014, blogs play a similar role – although differ in one respect in that they are (supposedly) run at an arm’s length from the party itself.

In 2014 terms, this could be interpreted as the difference between using Cameron Slater/Whaleoil to talk aggressively to committed supporters, and using more innocuous general sites such as www.teamkey.co.nz and www.national.org.nz to talk to voters at large.

Lesson 3: learning from US politics

In Dirty Politics (especially pp. 18-19) and in press coverage, author Nicky Hager points to the US as the origin of the tactics he alleges are being used by the Whaleoil blog and associates. From a press release on Scoop:

There have been repeated political attacks launched by the National Party attack dogs, notably Slater backed up by Farrar, and what the book shows is that many of these lead back to the Beehive. This is a technique originally from US republican politics known as a two-track strategy, where the prime minister maintains a friendly, relaxed public image while relying on political proxies to relentlessly attack opponents. This approach has meant that Key and his government have not had to take responsibility for their negative politics.

In another chapter of the book, on Kiwiblog author David Farrar, Hager cites an International Democratic Union (IDU) conference in Florida as an inspiration for NZ right-wing blogs, or in his words a “blueprint for what Whale Oil and Kiwiblog would become (pp. 99-100). David Farrar dismissed these claims in his initial response to the book.

What is Simon Lusk’s interest in US politics? Nicky Hager describes an e-mail from Lusk to him written after the publication of The Hollow Men, which recommended an article on tactics from the 1988 George H.W. Bush presidential campaign.

In Ecampaigning, examples from the international environment are often used for comparison and contrast. These include Australian, British and US examples. Lusk writes approvingly of the George W. Bush 2000 campaign website, which he ranks as “high” for quality of graphics, site design and technical features. He comments:

Bush’s site makes the best use of text of all political web sites. There is information in appropriate depth – summaries backed up by more detailed information for those who are interested in it. The Policy Points Overview is a great feature, with succinct information about where Bush stands on a variety of issues….

It should not be possible for someone to leave the Bush web site not knowing what Bush stands for.

It should be noted that Lusk also writes favourably about the Al Gore 2000 campaign website and others, so it is not necessarily the case that he was blinded by US Republican strategy. But taken together with the e-mail to Hager, it does indicate that Lusk is very open to learning from and applying political methods of other countries, particularly from the United States.

What does Simon Lusk have to say about the thesis?

I contacted Simon Lusk to ask him for comment on his thesis. He responded “Thanks for your message. It is the hunting season so I am unavailable for comment”.

I also asked David Farrar, who is named as a recipient of the discussion document on the National Party’s new website in the thesis, for comment about whether Peter Smith and Paul Smith (National’s Information Technology Manager) were the same person. He responded:

Peter Smith would not be Paul Smith. Paul is not involved and was a professional staffer, not a party person. He’s been out for 10 years or so. He did know Simon and would have exchanged some emails when he did work for Nats so can’t be 100% sure, but AFAIK [as far as I know] he is not involved in politics at all today.

In the end I don’t know who Peter Smith is, but again Paul is long out of politics.

I have been unable to locate contact details for Lusk’s supervisor, Bob Catley.

I would be very happy to publish any comment in future from Simon Lusk or those who know him. Please get in touch via the comments below or via the contact form.